By: Barry Prentice

A proposal to build an ice road from Churchill to Rankin Inlet, Nunavut, has been presented with the endorsement of both federal and provincial politicians. Manitoba Infrastructure and Transportation Minister, Steve Ashton, is quoted as recommending seasonal roads: “They are dollar for dollar one of the most cost-effective transportation initiatives you can bring into place.”

He might be right, but under what conditions and compared with what means of transport? The Nunavut ice road provides a case for comparison with one of the several cargo carrying airships that are being proposed.

In prior assessments of cargo airships and ice road trucking, this author excluded the costs of building and maintaining the seasonal infrastructure. Provincial bureaucrats advised that even if no trucks were used to carry goods to the remote communities, ice roads would still be built because of social issues. First Nations residents look forward each year to this brief period when they can visit friends and relatives in the otherwise remote communities. Consequently, airship cost comparisons were limited to the direct costs of ice road trucks.

In the case of building a new ice road connection between Manitoba and Nunavut, the “social road” argument does not hold. This allows the total cost of the 650-kilometre ice road for freight to be compared to a 463-kilometre flight for a cargo airship service.

The economic model for this analysis is set out in a forthcoming paper that compares the costs of airships and gravel roads. Key variables in the model are adjusted to reflect the lower construction costs of ice roads and the higher freight rates charged by ice road truckers.

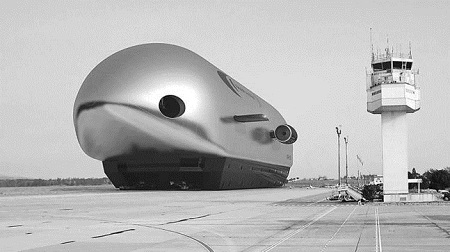

The airship used in the model is the VariaLift ARH-50. According to data provided by the developer, this all-metal, rigid airship could fly three cycles per day between Rankin Inlet and Churchill. The annual fixed costs of $8.3 million include the aircraft lease, insurance and staff. A hangar that could handle up to 25 airships adds $3.2 million to annual fleet costs. The variable costs per trip are $7,782.

The airship carries 50 tons and is assumed to operate 300 days per year.

Freight rates on ice roads are set competitively. In 2013, ice road truck rates are about 2.5 times the rates paid for these trucks on all-weather roads. In addition, fuel surcharges could be higher on a new ice road farther north. In this model, trucks rates are $0.32 per ton-kilometer, based on an empty return.

Utilization is the key to the economics of infrastructure. The cost of the Nunavut ice road is estimated to be $25 million build, and $12 million to rebuild it every year. The average cost of the ice road is determined by dividing the total public expenditure by the number of trucks.

The graph presented here shows the results of the economic model in which the ice road is assumed to operate 90 days each year. The straight line is the total cost of the ice road and trucks. The jagged line is the costs of the airships. Each “step” represents the addition of another airship to the fleet. As can be seen in this comparison, the ice road is more expensive to operate until the traffic volume averages 40 truckloads per day. The third and fourth airships continue to offer competitive rates until truck volumes exceed 88 vehicles per day; thereafter, the truck-ice road costs are less than the airship.

The volumes moved by trucks in the 90 days are spread out over 300 days in the airship. More frequent delivery reduces logistics costs. Holding inventories for up to nine months can add 10 to 25 per cent to the cost of using the ice road. Seasonal roads also lead to construction delays that could be avoided with year-round airship service.

Roads and airships are more complementary than competitive. Airships can fly anywhere and operate without ground infrastructure. Airships can be a pioneer mode of transport that builds the traffic to the point where the economics favor the construction of an ice road, or at higher volumes, an all-weather road.

Airships could lower the cost of building all-weather roads by relocating heavy equipment and moving bridge sections. Once the road opens, the airship can serve as a feeder system to augment the traffic on the road.

No one disputes the need for better transportation linkages to the North. Public road infrastructure is expensive to build and costly to maintain. The privately owned airship is the “infrastructure.” This fact alone should give governments with budget deficits cause for interest. Let’s hope that cargo carrying airships are included in future transportation planning and evaluation.

Barry Prentice is a professor of supply-chain management at the University of Manitoba.

Source: Winnipeg Free Press