Read two articles regarding the progress that Google is making on Project Loon, a system of stratospheric helium balloons to provide Wi-Fi connectivity to remote areas.

Read two articles regarding the progress that Google is making on Project Loon, a system of stratospheric helium balloons to provide Wi-Fi connectivity to remote areas.

Source: The Independent – independent.co.uk

Up, Up and Away on Google’s Wi-Fi Balloon

By: Will Oremus

Experts scoffed at the company’s plan to deliver internet via balloon to the world’s poorest regions. Now 75 are flying high

The majority of people in the world lack access to the internet. Either they can’t afford a connection, or none exists where they live. Of all the efforts to bring those people online, Google’s “Project Loon” sounds the most far-fetched.

When the search company announced in June 2013 that it was building “Wi-Fi balloons” at its secretive Google X labs to blanket the world’s poor, remote and rural regions with internet beamed down from the skies, expert reaction ranged from the skeptical to the dismissive, with good reason. The plans called for Google to put hundreds of solar-powered balloons in the air simultaneously, each coordinating its movements in an intricate dance to provide continuous service even as unpredictable, high-speed winds buffeted them about.

“Absolutely impossible,” declared Per Lindstrand, a Swedish aeronautical engineer and perhaps the world’s best-known balloonist, in an early Wired article about the project. “Just talk to anybody in the scientific community.”

Specifically, he poked holes in Google’s claim that it could build balloons durable enough to remain aloft for more than 100 days – nearly twice the duration achieved by state-of-the-art NASA balloons. “Even three weeks is very rare,” Lindstrand scoffed.

And yet, as you read this, some 75 Google balloons are airborne, hovering somewhere over the far reaches of the Southern Hemisphere, automatically adjusting their altitudes according to complex algorithms to catch wind currents that will keep them on course.

By 2015, Google believes it will be able to create a continuous, 50-mile-wide ring of internet service around the globe. And by 2016, Project Loon director Mike Cassidy anticipates the first customers in rural South America, Southern Africa, or Oceania will be able to sign up for 4G service provided by Google balloons. (Google is starting in the Southern Hemisphere, which is relatively sparsely populated, before expanding elsewhere.) But wait, I ask him, not wanting to get taken in by the techno-optimism that infuses so much of what Google does these days: what are the chances this will really happen?

“When I first started on this project, I would have said, like, 5 per cent,” Cassidy says. “But we’re getting further and further, and what’s amazing is that we haven’t found anything that could keep it from working yet. You know, nothing in life is 100 per cent certain. But it’s looking pretty good.” How Google has come this far is a study in the power of perseverance – and the power of a company whose resources, leeway and technological ambitions have few rivals in the annals of global capitalism.

If Lindstrand were there to see the company’s first attempts to launch its super-pressure balloons in New Zealand last summer, he might have laughed. On the first try, the balloon burst not long after lift-off. The same happened on the second try, and the third – and the next 50 after that. The team kept tweaking the fabric and reinforcing it with more Kevlar-like ropes, but the balloons kept bursting until they got the length of the ropes exactly right.

“We knew it was hard to make a super-pressure balloon,” Cassidy recalls. “We didn’t think it would take us 61 attempts until we succeeded.” Even then, the success was short-lived. Instead of bursting, the balloon slowly leaked helium, bringing it down after just a day or two in flight. Google’s engineers spent weeks trying to isolate the problem. They took balloons out of their boxes and inflated them in a cavernous hangar, shined polarized light through them, and even sniffed for helium leaks using a mass spectrometer. Each balloon that went down was subjected to a “failure analysis” that included poring over meticulous records of who had assembled it, where and using what equipment, and how it had been transported.

Project Loon: Getting internet into remote areas of the world is tricky, but Google think that balloons might be the answer. They’ve proposed a network of high-altitude weather balloons that could deliver high-speed wireless internet. Early tests in New Zealand have been successful, but the project has also been criticized for its perceived triviality.

Eventually, they pinned the leaks on two sets of problems. One was that the balloons had to be folded several times over to be transported, and some developed tiny tears at the corners where they’d been folded repeatedly. Google set to work finding ways to fold and roll the balloons that would distribute the stress more evenly across the fabric. The second problem was that some balloons were ripping slightly when workers stepped on the fabric with their socks. The solution to that problem? “Fluffier socks,” says Cassidy. “Softer socks meant fewer leaks.”

As the team cut down on the leaks, the balloons started lasting longer: four days, then six, then several weeks at a time. As of last November, two out of every three balloons remain in the sky for at least 100 days. But keeping the balloons airborne is only the first of the monumental problems that the project presented. Keeping them on course may be even harder.

When Google first announced the project, I pictured brightly coloured vessels hovering in place a few hundred or thousand feet over their respective target villages, perhaps tethered to the world’s longest ropes. The reality is far more complex – and fascinating.

First of all, the balloons rise more than 18,000m (60,000ft) above the Earth’s surface, putting them far beyond the reach of the highest-flying aircraft – and atmospheric storm systems. That’s much too high to be visible from the ground. Secondly, the balloons could never hover in place. They’re constantly propelled by stratospheric wind currents that can reach up to 100mph. That’s a little problematic, given that the aim is to provide steady data service to stationary targets back on solid ground.

Google’s solution is to keep large fleets of balloons aloft at all times, with some following in others’ wakes. That way, just as one balloon is about to drift out of range of a given location, the next one is entering the zone, keeping the connection alive. That would be a tricky enough ballet with high-powered aircraft that could steer themselves along precise paths. But again, these are low-powered balloons, and there’s no way to directly control their trajectory.

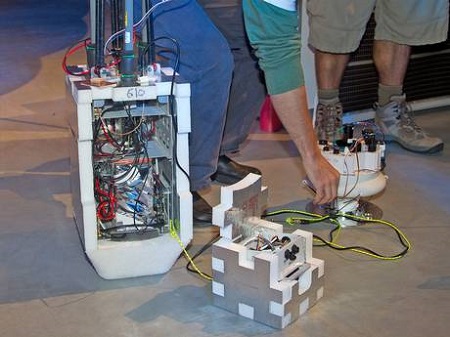

The Project Loon communications unit, right, with the altitude controller, center, and Avionics bay.

Photo source: GettyAll you can do is adjust their altitude. “Steering”, then, involves projecting the wind speeds and directions at different altitudes, and maneuvering the balloons up and down in hopes of catching a succession of currents that will approximate the path you’re aiming for.

Google’s engineers knew that would be difficult going in, and they planned to rely on wind velocity data from the US National Weather Service’s weather balloons and archival records. What they didn’t anticipate was just how unpredictable those wind currents can be. An embarrassing example of the problem came when Google was performing a high-profile demonstration of its balloons in Brazil in May, in front of the country’s communications minister and the president of Telefónica, the Spanish telecoms provider.

“You know how they say, ‘Never do a live demo?’ ” Cassidy says. “The first balloon went up and we told them, ‘Look, our simulations show that the balloon’s going to go this way.’ Everybody looked – and the balloon went the other way.” Google’s red-faced project leaders quickly ordered the wayward balloon brought down and dispatched a truck to retrieve it, some 12 miles away. They sent up a second balloon, and this time the winds co-operated. Students at a local school successfully logged on.

It seems clear that Google has the potential to deliver on its promise. Whether it proves to be worth all the effort will depend on how fast and reliable that service is and how much it costs to keep it going.

The original idea was to broadcast Wi-Fi from the balloons to base stations on the ground. But Google quickly realized that the power limitations outweighed the advantages of the unregulated spectrum. Instead, the company began to partner with telecommunications companies to broaden their existing cellular networks using the same LTE protocol.

By contracting with telecoms to provide the service, Google removes itself from the sales and customer-service end of the cellular-data equation, and from the country-by-country battle for rights to the 2.6 GHz spectrum. The company is famously far more interested in solving complex engineering problems than it is in dealing directly with consumers or lobbying government agencies.

Providing internet access via a fleet of algorithmically directed balloons may sound prohibitively expensive, but Cassidy says it’s actually an order of magnitude cheaper than setting up and maintaining cell towers, making it more economically viable in remote regions. And while the quality of service will never match that of, say, Google Fiber, Cassidy is convinced that the company can make it a vast improvement over what many parts of the world have today. “We’ve visited villages where people get their internet from a Wi-Fi hotspot on an inter-city bus,” he says. “As the bus rolls in, everybody’s phone suddenly will download its messages. And the bus will drive to the next village.”

If Project Loon succeeds, Google’s project will soon face a new set of questions – one that its doubters never thought it would have to ask. Questions such as: will it be profitable? And: should countries trust Google with their stratospheric airspace? In a June follow-up with Wired, Google X chief Astro Teller called Project Loon “the poster child for Google X.” The team has done a remarkable job so far. The next test will be how it handles the pressure of turning hot air into a business.

Source: The Independent – independent.co.uk

—————————————————————————————–

Source: Aviation Week – aviationweek.com

Google, France Partner on Balloon-Powered Internet

By: Amy Svitak – Aerospace Daily & Defense Report

French space agency CNES will join Google in the online-search giant’s ambitious project to launch a fleet of stratospheric balloons to provide Internet access to rural and underserved parts of the globe.

Dubbed Project Loon, the fleet of balloons would be carried by winds some 18 to 20 km above the Earth – higher than commercial airlines and weather – and powered by solar panels.

Using a two-way link, Internet signals would be transmitted up to the balloon from the ground and relayed to other balloons before being sent back down, where they would be picked up by outside antennas or LTE-enabled phones.

CNES, which is supporting the project with balloon engineering expertise acquired over the past 50 years, says the connection speed would be fast enough to stream videos.

“Collaborations like this bring down barriers and spawn new cross-disciplinary projects,” CNES President Jean-Yves Le Gall said in a Dec. 11 news release announcing the venture. “We are proud to be providing our expertise while benefiting in return from the assistance of such a great global company.”

CNES will contribute to ongoing balloon flight analysis and development of next-generation balloons. With help from Google, CNES will conduct Strateole-type long-duration balloon campaigns similar to the Concordiasi balloon project in 2011, but with a wider stratospheric coverage.

“Internet connectivity can improve lives, but more than 4 billion people still don’t have access today. No single solution can solve such a big, complex problem,” said Mike Cassidy, Google vice president in charge of Project Loon. “That’s why we’re working with experts from all over the world, such as CNES, to invest in new technologies like Project Loon that can use the winds to provide Internet to rural and remote places.”

Project Loon began in June 2013 with an experimental pilot in New Zealand that was followed by additional tests in California and northeast Brazil.

Less expensive to launch and operate than satellites, stratospheric balloons filled with hydrogen or helium can carry several hundred kilograms to 40 km altitude for 24 hr.

In some cases, payload nacelles can be recovered from the balloons and reused, with the same instruments or sensors flying two or three times in a matter of days during a campaign, in some cases. In addition, balloons can be launched with simple infrastructure from a variety of locations.

CNES has been designing, manufacturing and releasing atmospheric balloons for three decades, developing a variety of platforms adapted for exploration. The agency currently employs a staff of 60 dedicated to balloon research at two main sites, in Toulouse and Aire-sur-l’Adour in southwestern France. The program costs on average about 1.2% of France’s annual total space budget.

Source: Aviation Week – aviationweek.com