Source: Albuquerque Journal – abqjournal.com

Source: Albuquerque Journal – abqjournal.com

By Rick Nathanson

Between the years 1550 and 1900, more than 500 people were lost or killed trying to get to the North Pole, mostly by sailing ships or pulled on sledges by dogs or Siberian ponies.

But in 1897, three fearless and forward-thinking adventurers from Sweden, attempting to become the first to successfully cross that Arctic holy grail, set off on an expedition via the never-before-tried conveyance of a gas balloon.

Count them among the 500.

Not only did they perish far short of their goal, but their bodies weren’t discovered for 33 years.

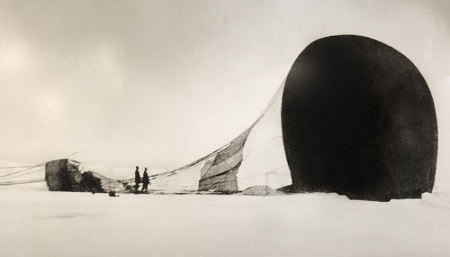

This image was taken by one of the Swedish explorers during a failed 1897 attempt to cross the North Pole in a gas balloon. The fate of three explorers was unknown until their remains and their camera were accidentally found 33 years later. The photo is one of many included in “Arctic Air: The Bold Flight of S. A. Andrée,” an exhibition at the Anderson-Abruzzo Albuquerque International Balloon Museum.

A re-creation of the aeronaut’s camp on the polar ice. Their bodies were discovered thirty three years after their ill fated flight.

Photo: Dean Hanson – Albuquerque JournalTheir story is the subject of an exhibition at the Anderson-Abruzzo Albuquerque International Balloon Museum, “Arctic Air: The Bold Flight of S.A. Andrée.” The display recounts the tale using interactive touchscreens, videos, text panels, newspaper articles, period appropriate artifacts, a replica of the balloon, excerpts from the explorers’ journals, and photos taken with a camera that was found buried in the ice among their remains.

Museum curator Marilee Schmit Nason said that expedition leader S.A. Andrée was head of the patent office in Stockholm; crewman and meteorological observer Knut Fraenkel was a mechanical engineer; and second-in-command Nils Strindberg was a physics teacher, who for the journey designed a special camera with interchangeable lenses, a compass and instrumentation to determine the orientation of the camera as well as the date and time.

Andrée procured funding for the expedition primarily from King Oscar II of Sweden, chemist-philanthropist Alfred Nobel, and merchant-industrialist Oscar Dickson, considered the wealthiest man in Sweden at the time. The total investment would be about $1 million in today’s U.S. currency, Nason estimated.

In addition to bragging rights as being the first to cross the North Pole, Andrée pitched the enterprise as scientific. The team would do aerial photography for future mapping of the region and look for an ice-free passage through the Arctic.

They also planned to take samples and conduct observations to determine the presence of precious metals or minerals in the Arctic, and conduct research on ice flow and Arctic weather.

A replica of Örnen (Eagle) with balloonists S.A. Andree, Nils Strindberg and Knut Fraenkel commemorates their ill-fated attempt to reach the North Pole by balloon in 1897, in the new exhibition “Arctic Air: The Bold Flight of S.A. Andree” at the Anderson-Abruzzo Albuquerque International Balloon Museum.

Photo: Dean Hanson – Albuquerque JournalOn July 11, 1897, the adventurers launched their balloon, Örnen (Eagle), from Danes Island in the Svalbard Archipelago in northern Norway. The hydrogen balloon design used by Andrée featured an enclosed wicker gondola wrapped in canvas. A hatch door at the top of the gondola opened to an observation deck with some storage.

The balloon had two innovative add-ons – a heavy drag rope to help regulate altitude and speed, and sails to help steer the aircraft.

Neither worked as planned, Nason said. Early into the flight, the drag rope fell off, and the fixed sails had little effect in determining direction of travel.

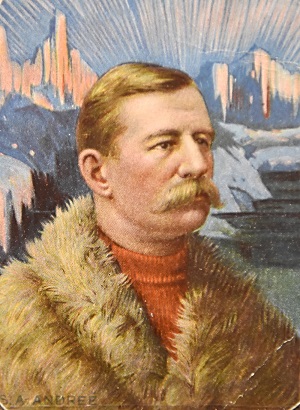

A historic portrait of S.A. Andrée, leader of an expedition of Swedish explorers who attempted to cross the North Pole in a gas balloon in 1897.

Photo: Dean Hanson – Albuquerque Journal“They wanted to keep a constant 500 feet above the ice as much as possible, but when the drag rope broke away the balloon rose to 700 meters,” or about 23,000 feet, Nason said. “Then a layer of ice formed on the envelope and the weight forced the balloon back down. The explorers began throwing out ballast and equipment to lighten their load.”

The cycle of ascent and descent continued unabated, and at one point the gondola was knocked about and dragged along the ice, she said.

On July 14, a mere 295 miles and 65 hours into their flight, the balloonists conducted a controlled landing and decided to walk out.

Each attached himself to a harness and pulled his own sled loaded with supplies – including clothing, food, camping equipment, scientific instruments and a collapsible boat with a canvas hull. Because the ice sheet beneath them was moving in the opposite direction, they often made little progress, even after walking days on end.

On Oct. 6, the men finally found themselves on remote White Island, part of the same archipelago from which they launched.

Throngs attended the 1930 state funeral in Stockholm for the three Swedish aeronauts who attempted to cross the Arctic in a gas balloon in 1897. The discovery and return of the bodies, 33 years after the men were lost, set off a national period of mourning in Sweden.

Photo: Dean Hanson – Albuquerque Journal“During the three months they walked across the ice they kept diaries, so we know how many times they fell down, who got ill, what they ate every day, and then all of a sudden we have nothing,” Nason said.

The last journal entry was Oct. 7, the day after they set up camp.

Despite two search teams dispatched to look for the balloonists, their fate was unknown until Aug. 6, 1930. An unusually warm summer had melted the snow that nearly always surrounded the island and allowed a Norwegian seal and walrus hunting vessel to land a party. There, they discovered the remains of the three men and what was left of their encampment.

Among the finds were Strindberg’s camera, some of the earliest rolls of Kodak film, and the men’s journals, which were stuffed inside the coat Andrée was wearing when he was frozen in time – sitting on a ledge as if scanning the horizon for the rescuers who arrived 33 years too late.

‘Arctic Air’ exhibit

A new long-term exhibition at the Anderson-Abruzzo Albuquerque International Balloon Museum, “Arctic Air: The Bold Flight of S.A. Andrée,” chronicles the ill-fated 1897 attempt by three Swedish explorers to cross the North Pole.

Admission is $4 for adults ($1 discount for state residents); $2 for seniors; $1 for children age 4-12; and free for 3 and younger. Admission is free every Sunday from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m., and on the first Friday of every month.

The museum is open year-round, Tuesday through Sunday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Source: Albuquerque Journal – abqjournal.com