Source: The Telegraph/macon.com

Source: The Telegraph/macon.com

By Jim Gaines

A model ship in a large glass display case dominates the lobby of the former Macon City Hall: the USS Macon, a World War II-era cruiser named for the city.

Yet that was not the only USS Macon. Another U.S. Navy vessel, even larger than the 674-foot warship, plied the skies a decade before the cruiser was commissioned.

Despite that, no local monument stands to the rigid-framed, helium-filled dirigible that crashed into the Pacific Ocean on Feb. 12, 1935.

The flying USS Macon was a bold experiment, leading-edge technology for its time, said Bill Stubkjaer, curator of the Moffett Field Museum in Sunnyvale, Calif.

During its short working career, the airship was based at the field later named for U.S. Navy Adm. William Moffett, an advocate of airships killed in the 1933 crash of the USS Akron, the USS Macon’s sister ship.

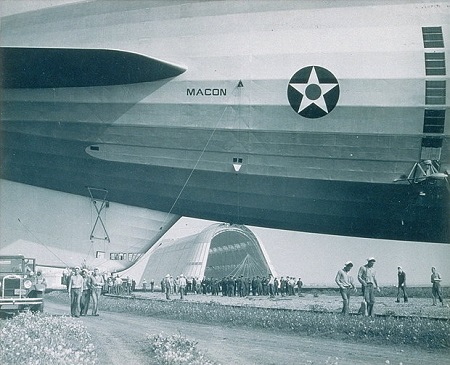

The USS Macon arrives in Sunnyvale, Calif., in 1934. The airship’s framework gave way in a storm, and it crashed off the California coast in 1935.

Photo: U.S. NavyAt one time, years ago, a large photograph of the airship USS Macon – designated the ZRS-5 – hung in City Hall, recently renamed the Macon-Bibb County Government Center. But where that picture went, no one seems to know.

Commissioner Ed DeFore, who served 42 years as a Macon city councilman before taking a seat on the new Macon-Bibb County Commission, said he has a vague memory of it as one of many displays that cycled through City Hall. A picture may also have hung at the city’s Downtown Airport, he said.

But airport manager Doug Faour said someone familiar with local aviation history told him the USS Macon’s picture was displayed at City Hall and not at the airport.

Nor is it commemorated at the Museum of Aviation in Warner Robins, said Bill Paul, the museum’s collections manager.

“I don’t think we really have anything on it,” he said. But there are a few things at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Fla., Paul said.

The naval aviation museum’s online archives list a skyhook from one of the USS Macon’s airplanes and a metal wheel, both retrieved from the airship’s wreck. The USS Macon carried four Curtiss F9C Sparrowhawk biplanes, which hooked onto the airship’s underside.

Mayor Robert Reichert said he knew of the airship’s existence but little more.

“I haven’t even seen good pictures,” he said.

As to where the old photo might have gone, a clue may lie in the model of the other USS Macon. The cruiser model is actually on loan from the U.S. Navy Archives, Reichert said.

“It is their property, not the city’s property,” he said.

Taking note of the cruiser is sufficient, but if a good picture of the airship turned up, Reichert said, he wouldn’t mind putting it on display. But at an original 785 feet long, a model of the airship on the same scale as the cruiser wouldn’t leave any room in the Government Center lobby, he said.

In 1991, the USS Macon’s wreck was rediscovered 1,500 feet deep in the Pacific Ocean by the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute. The site is on the National Register of Historic Places, but it’s off limits to divers.

The last known survivor of the USS Macon’s crew died four or five years ago, Stubkjaer said.

The USS Macon is seen here in 1934 at Naval Air Station Sunnyvale, Calif. In 1991, the USS Macon’s wreck was rediscovered 1,500 feet deep in the Pacific Ocean by the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute. The crash ended the Navy’s large rigid airship program.

Photo: U.S. NavyAt Moffett Field today the skeleton of the USS Macon’s hangar remains, and the museum has one room dedicated to the airship, Stubkjaer said. Most of the exhibits are pictures, but there’s also a model of the airship and a few artifacts from its wreck, he said.

About 2,000 people each year tour the airship exhibits. A few have come from Akron, Ohio, Stubkjaer said, but he doesn’t recall any from Macon.

“We do occasionally get somebody who says, “Oh yeah, I remember seeing it in the air,’ ” he said.

The museum has a picture of a silver platter and bowl given for use on the airship by the city of Macon in 1933, Stubkjaer said. Such presentations were common then. If the platter and bowl were on board when it crashed, they’re still at the bottom of the ocean, he said. But if they were on land at the time, it’s possible the silver service made its way back to Macon, he said.

Rigid-framed airships were first widely used by Germany during World War I. But it was concern about the expansion of Japanese power in the Pacific that really drove American interest in long-range, lighter-than-air ships as long-range scouts, Stubkjaer said.

“Basically, the way you found the enemy fleet was to go out and look for them,” he said.

In the 1920s, the U.S. built the USS Shenandoah and bought the R-38 from Great Britain; but they both crashed, Stubkjaer said. The USS Los Angeles was bought from Germany. It didn’t crash but was too small to be effective as a long-range scout, so it was relegated to training use, he said.

Then the Navy ordered a pair of airships from the Goodyear Zeppelin Corp., as prototypes for many more, Stubkjaer said. Those two would become the USS Akron and the USS Macon. The first built was the USS Akron, named for its city of construction and based in Lakehurst, N.J., he said.

The USS Macon’s name, the story goes, was more political in origin, Stubkjaer said. At the time, Macon was the largest city in the district of U.S. Rep. Carl Vinson, D-Ga.

“He was very much an ally of the Navy,” Stubkjaer said.

Supposedly Vinson was running for re-election, and an opponent questioned why Vinson couldn’t get vessels named for locations in Georgia if he was so influential. So, at Vinson’s urging, the new airship bore Macon’s name though it never landed in the city, Stubkjaer said.

“I think it may have flown over (Macon) once,” he said. “So there wasn’t a whole lot of deep connection.”

The USS Akron launched in August 1931 and crashed in an Atlantic storm in April 1933. Just three of the 76 crewmen survived, among them Cmdr. Herbert Wiley, who later commanded the USS Macon.

The USS Macon launched a month after the USS Akron’s loss. It flew from its construction site in Akron to Lakehurst, and then cross-country to its permanent base in Sunnyvale, Calif., Stubkjaer said.

For more than a year it joined in fleet exercises, but on Feb. 12, 1935, the USS Macon’s framework gave way in a storm, and the airship went down off Point Sur, Calif. This time, however, just two crewmen were lost.

The crash ended the U.S. Navy’s large rigid airship program, especially as longer-range search planes and floating aircraft carriers were produced during World War II, Stubkjaer said.

“It was simply a lot cheaper to build airplanes than it was to build large rigid airships,” he said. “The rigid airship could never hold as many aircraft as an aircraft carrier. By the end of the war, the large rigid airship really had no advantage.”

Source: The Telegraph/macon.com