Source: Akron Beacon Journal – ohio.com

Source: Akron Beacon Journal – ohio.com

By Mark J. Price – Beacon Journal staff writer

Akron added an important word to its lexicon 100 years ago.

Dr. William C. Geer, vice president of the B.F. Goodrich Co., called a staff meeting in 1917 to announce the exciting news that the Akron company would bid on a blimp contract for the U.S. Navy.

Looking around the room, Geer noticed confused looks. Finally, John R. Gammeter, a process engineer, piped up: “What the hell’s a blimp?”

Although Akron residents were familiar with dirigibles, the British slang term “blimp” for a nonrigid airship hadn’t drifted into the local vocabulary. That was about to change.

On March 12, the Navy ordered two blimps for $83,000 from Goodrich and nine for $300,000 from Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., a rival Akron company. The Goodyear blimp is iconic today, but some local residents might be surprised to learn that Goodrich made blimps, too. Gammeter, a mechanical genius who had owned the first airplane in Akron, was placed in charge of aeronautical work at Goodrich just before the United States entered World War I.

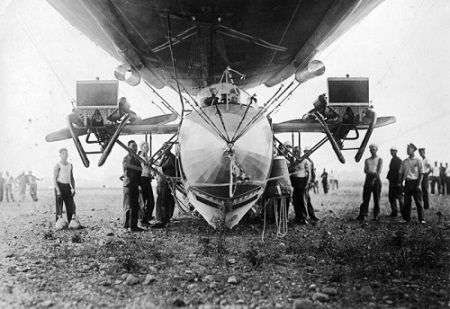

U.S. Navy blimp C-2 was built in Akron by the B.F. Goodrich Co. during World War I. Yes, there really was a Goodrich blimp.

Photo: B.F. Goodrich Co., University of Akron Archival Services.“In 1917 I went to Washington with Dr. William C. Gear, chief chemist of Goodrich,” Gammeter recalled years later. “P.W. Litchfield was there from Goodyear, and the Curtiss people from Hammondsport. Commander J.C. Hunsaker of the Navy wanted eight blimps. He agreed to split it. Doc Gear offered to build four blimps, but I kicked him under the table. ‘Two, two,’ I whispered.”

Goodrich brought French aeronautical engineer Henri Juilliot, 60, to Akron to oversee construction of airships. Juilliot, who reportedly was paid $2,000 in gold, gathered a crew of mechanics, chemists, engineers, riggers and seamstresses.

“The United States will need many dirigibles in case of hostilities with Germany,” Juilliot noted upon arrival in Akron. “They are essential for coast defense. The larger dirigibles can go out to sea for 500 miles and watch for enemy fleets.”

Built to Navy specifications, the cigar-shaped airships were 160 feet long, 50 feet high and 31 feet in diameter with a capacity of 77,000 cubic feet of hydrogen. The Curtiss Airplane Co. of New York supplied the gondolas and 100 horsepower engines. The blimps could travel 45 mph and soar to an elevation of 7,500 feet.

The Curtiss Airplane Co. of New York furnished two-man gondolas as the B.F. Goodrich Co. of Akron built eight airships for the U.S. Navy during World War I.

Photo: B.F. Goodrich Co., University of Akron Archival Services.“To become an operator of a military dirigible, one must have youth, a month’s training and a working knowledge of physics and mechanics,” Juilliot explained.

The federal government obtained permission to use Fritch Lake near the Portage County line as a testing field for Akron-made airships. Construction of a blimp hangar was expected to take 60 days to complete. Today, Fritch Lake is known as Wingfoot Lake, home of the Goodyear blimp.

After U.S. entry in the war on April 6, 1917, the Navy needed Akron airships to patrol the Atlantic coast and perform anti-submarine duty in the North Sea. Each blimp could carry more than 6,000 pounds of explosives. Overseas, German zeppelins were used to scout enemy positions and carry out bombings.

Goodyear was the first to make test flights in June 1917 with pilot Ralph Upson and engineer Herman Kraft aboard. During a voyage from Fritch Lake to Akron and back, Upson waved from 500 feet up when he spied his wife on the porch of their Goodyear Heights home.

“On the buildings and lawns of Akron a strange shadow was cast Monday morning, as between the city and the sun silently glided one of the big factors of war, a dirigible balloon,” the Beacon Journal reported June 25.

“As Akron people gazed upward there came to the minds of many the realization of the feeling of fear and awe which must fill the hearts of those in England and France when a shape similar to the one that sailed over Akron rains death and destruction.”

Although Goodyear’s blimp flew first, Goodrich’s blimp was the first to win approval from the government. The air bag was built in Akron and towed to Chicago for inflation at a hangar. Gammeter designed a pressure-relief valve that became the standard for U.S. blimps for decades.

“One morning I came out to the hangar and snapped my finger against the blimp,” Gammeter recalled. “ ‘Ain’t she a beauty?’ I said to the cop. ‘Keep your hands off that,’ he said. ‘It belongs to Uncle Sam.’ ”

Goodrich hired balloonist Roy Knabenshue to test a blimp for the Navy in a secret night flight over a nameless big city on the Atlantic coast.

“Over the metropolis the monster hovered, unobserved, unsuspected by the moving hordes of pedestrians, for eight hours,” the Beacon Journal reported Sept. 22, 1917. “Below, Roy Knabenshue, the pilot of this giant craft, saw the twinkling lights, saw the illuminations thrown out by the theaters, the cabarets, the restaurants — the drama of night life as enacted by dots, by a blurred mass.”

The government accepted Goodrich’s blimp and deployed it for homeland defense. Blimp A-247 was stationed at Montauk Point on Long Island, N.Y., where it established a record of 17 months and four days in service, covering 23,000 miles at sea and guarding convoys of U.S. ships against enemy attacks. When it was retired in March 1919, the Goodrich blimp was a hit attraction at an aeronautical expo in New York.

In all, Goodrich built eight blimps and 360 smaller observation balloons during the war. When the conflict ended, Goodrich ended its program over concerns about profitability. Its competitor Goodyear was far more enthusiastic, constructing at least 60 airships and 1,000 balloons during the war, and turning the blimp into a beloved corporate symbol.

Despite its proud service, the Goodrich blimp was reduced to a joke in the 1970s. The company hired Grey Advertising Co. of New York to launch a campaign titled “We’re the Other Guys!” “If you see an enormous blimp with somebody’s name on it, we’re the other guys,” Goodrich noted.

The company produced posters showing empty blue sky and the caption: “A picture of the Goodrich blimp.”

The University of Akron’s Archival Services division in the Polsky Building has preserved a fragile scrapbook with rare photos of the Goodrich airships being constructed 100 years ago. Tucked inside the cover is a note from executive William C. Geer to a blimp builder: “You might like to have a memento of the part you played in the enterprise.”

The Goodrich blimp was never a joke to those who worked on it.

Source: Akron Beacon Journal – ohio.com