By Mark J. Price

In the world of advertising, where the sky’s the limit, the Goodyear blimp took marketing to the next level.

The Akron company’s logo was as plain as day when the silver airship floated among the clouds. As darkness fell, however, no one could see it.

The solution to the problem was a flash of brilliance.

Preserved for 85 years, a typewritten note is tucked inside a folder among boxed files in the vast collection of Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. records at the University of Akron’s Archival Services in the Polsky Building.

“We would like to be able to light the sides of the non-rigid airships so that the name GOODYEAR on both sides of the ships can be distinctly seen at night,” blimp pilot Jack Boettner, manager of airship operations, wrote March 13, 1929, to Karl Arnstein, vice president and chief engineer. “This can probably be accomplished by flood lights mounted on outriggers or mounted on a base and attached to the envelope underneath the name. The name GOODYEAR on both sides of the ships would also be more effective if it were moved down below the equator line so that it could be easily and distinctly seen from an angle. This would also simplify the lighting proposition. Kindly advise me what can be done relative to the above at your earliest convenience.”

Arnstein’s team considered applying luminous or phosphorus paint to make the name glow on the envelope of the Defender airship at the Wingfoot Lake hangar in Suffield Township. Ultimately, engineers decided to use red neon tubing to write the company’s name in giant letters.

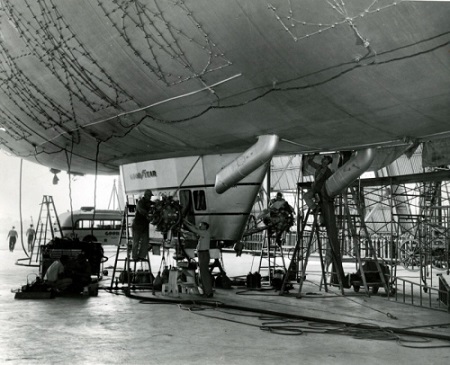

Goodyear blimp Mayflower is overhauled in 1949 at the Wingfoot Lake hangar in Suffield Township. The incandescent light framework attached to the envelope allowed the airship to spell out any letter or numeral at night on its giant advertising sign.

Credit: Akron Beacon JournalResearchers experimented for months with neon signs on the curved surface of the blimp. By necessity, the framework of tubing had to be lightweight. A gasoline-powered generator in the cabin provided illumination.

Finally, the sign was ready for a surprise test in public.

An unearthly, reddish glow rolled across the night sky Oct. 14, 1930, as the Defender hummed toward Goodyear President Paul W. Litchfield’s mansion, The Anchorage, on Merriman Road. The odd sight made spectators gape.

C.T. Hutchins, manager of the Goodyear advertising department, could barely contain his excitement in a letter to Harry E. Blythe, assistant to the president. “Tuesday night, just before going to the train, I watched for the Defender — and figured probably the best place to see it would be near Mr. Litchfield’s,” Hutchins wrote. “I stopped there just as it came over. Eddie Thomas came out, and we saw it together. I want to say it was wonderful. No doubt you saw it too. The flashing on and off was very effective. If we could get a sign that would look — at an altitude of 1,500 feet — like this sign did, flying low, then in my opinion we have the most effective advertising device this, or any other company has ever developed.”

Goodyear blimp Puritan uses its Trans-Lux sign to flash a special bulletin from the Beacon Journal newsroom in 1947. Goodyear called the process blimpcasting. The letters were 18 feet high.

Credit: Akron Beacon JournalGoodyear also installed the neon lights on Puritan, Reliance, Volunteer and Resolute. The word “TIRES” was added in neon so that it alternately flashed with “GOODYEAR.”

Silver Lake resident H. Webster Crum, a pilot, draftsman, designer and future chief engineer at Wingfoot Lake, improved the advertising system in 1932 under the catchy name Neon-O-Gram.

Instead of fixed words in lights, Neon-O-Gram provided a composite sign that allowed the display of any letter or numeral. Letters were 6 feet high, 4 feet wide and attached to the envelope on 10 aluminum frames. The system operated through hand-punched perforations in an endless loop of tape similar to a player-piano roll. Blimps could flash advertising slogans of six to 10 words.

Goodyear invited other companies to rent the neon signs at $250 per hour for a minimum of four hours.

“When people gaze aloft into the inky darkness of the night and see nothing but a flaring message, with the outline of a leisurely soaring blimp, at an altitude of 1,500 to 2,000 feet, there’s power to that kind of advertising,” Goodyear boasted in 1932 ad circulars. “There isn’t the slightest doubt that the attention value surpasses any other form of advertising.”

In November 1934, the Puritan flashed election returns over Akron, announcing the election of Kent’s Martin Davey as Ohio governor.

Commercial blimp advertising went on hiatus during World War II as airships were drafted into military service. The signage returned in 1947, however, with another catchy name: Trans-Lux.

Ten panels — each holding 182 incandescent lamps — were installed on both sides of the Puritan. The 18-foot letters traveled from right to left through banks of lights on a 190-foot surface.

Resembling a sign at Times Square in New York, the blinking lights flashed bulletins from the Beacon Journal newsroom after dusk. “The first evening the weather permits, you’ll be reading headlines in the sky,” the newspaper promised.

Goodyear called the process “blimpcasting.” It’s probably no coincidence that sightings of flying saucers skyrocketed that year.

As technology improved, so did the signs. The next catchy name was “Skytacular,” which was added to the airship Mayflower in 1966 and debuted at the Indianapolis 500. The incandescent sign used more than 3,000 red, green, blue and yellow lights to create patterns in the sky.

The next-generation sign, “Super Skytacular,” using more than 7,000 lamps for basic animation, was introduced three years later.

By the 21st century, LED technology replaced incandescent signs on Goodyear blimps. Eaglevision, another catchy name, used a computer-driven system to create dazzling video displays with more than 80,000 lights.

That was the system on the Spirit of Goodyear, which was decommissioned last month in Florida. The blimp is being replaced with a semi-rigid airship, Goodyear NT, whose construction is nearing completion at Wingfoot Lake.

Test flights are expected to begin this month. Longer, sleeker and faster than its predecessor, the new ship has yet to be named. “NT” stands for “New Technology.”

Will that technology apply to a new sign? You can bet for darn sure it won’t be neon.

Maybe a catchy name will be added to the lexicon.

Keep watching the skies.

Source: Akron Beacon Journal