Source: The National Archives – archives.gov

Source: The National Archives – archives.gov

The dramatic, fiery fate of the German rigid airship LZ-129, the Hindenburg, in 1937 is the most famous event of the airship age.

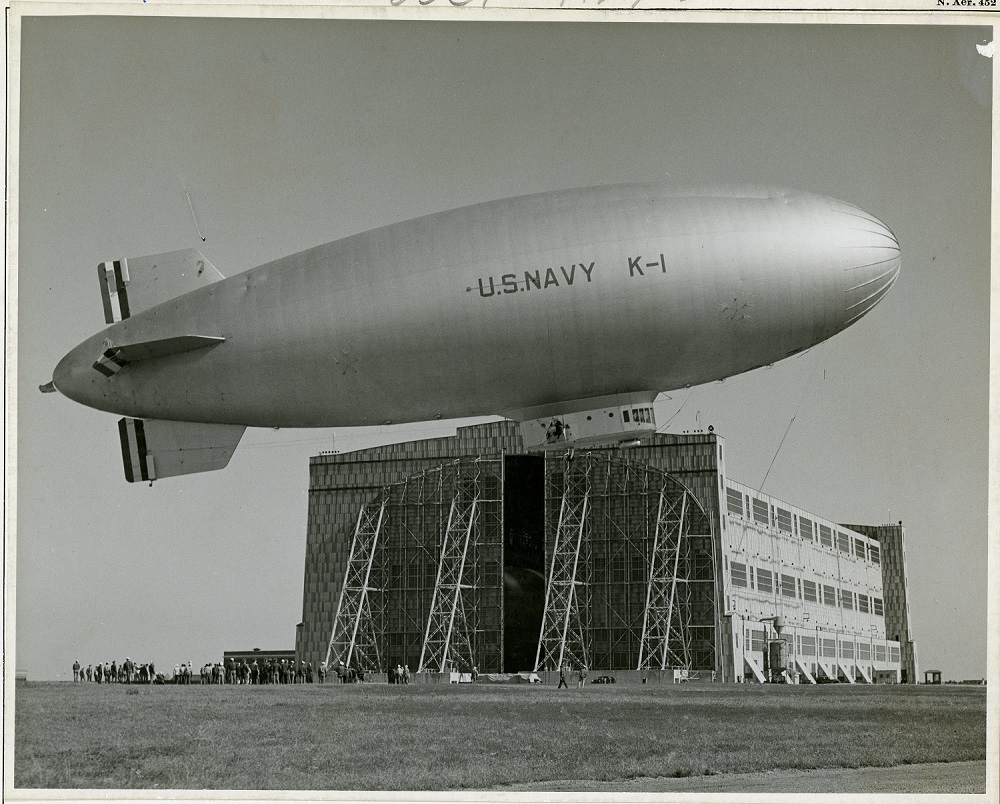

“K-1 Taking off N.A.S. Lakehurst,” October 1933.

General Records of the Department of the Navy, National ArchivesHowever there were great accomplishments both before and after the Hindenburg: airships broke some of the earliest flight records—the first successful nonstop transatlantic crossing and return, the first air travel with paying customers, the fastest circumnavigation of the globe, and, ignobly, the first aerial strategic bombing of civilians.

Regardless of the tragedy of the Hindenburg, large, rigid airships fell out of favor with most governments by the 1930s due to their cost, susceptibility to inclement weather, and accidents. Germany and other European nations favored hydrogen lifting gas, which was more readily available, cheaper, and had greater lifting power than helium. Following the 1921 disaster of the semi-rigid airship Roma, the United States used helium.

Helium is nonflammable and extractable almost exclusively from the United States and was considered a strategic and commercial asset. A 1927 amendment to the Helium Control Act of 1925 stated “no helium gas shall be exported from the United States . . . until after application” and approval from the President and the recommendations of the Secretaries of Commerce, War, and Navy.

Although the risk of combustion was greatly reduced, four of the five American rigid airships were still lost but due to bad weather. The surviving fifth one, the USS Los Angeles (ZR-3), was German-built and later dismantled.

Despite the safety record of German airships, that country’s dependence on inflammable hydrogen was an invitation to still more tragedies, and the famed “Zeppelins” were grounded by World War II. In a strange twist of history, the war brought about a new age of relevance for the smaller, less costly non-rigid airships, genially known as “blimps”—but to the advantage of the United States.

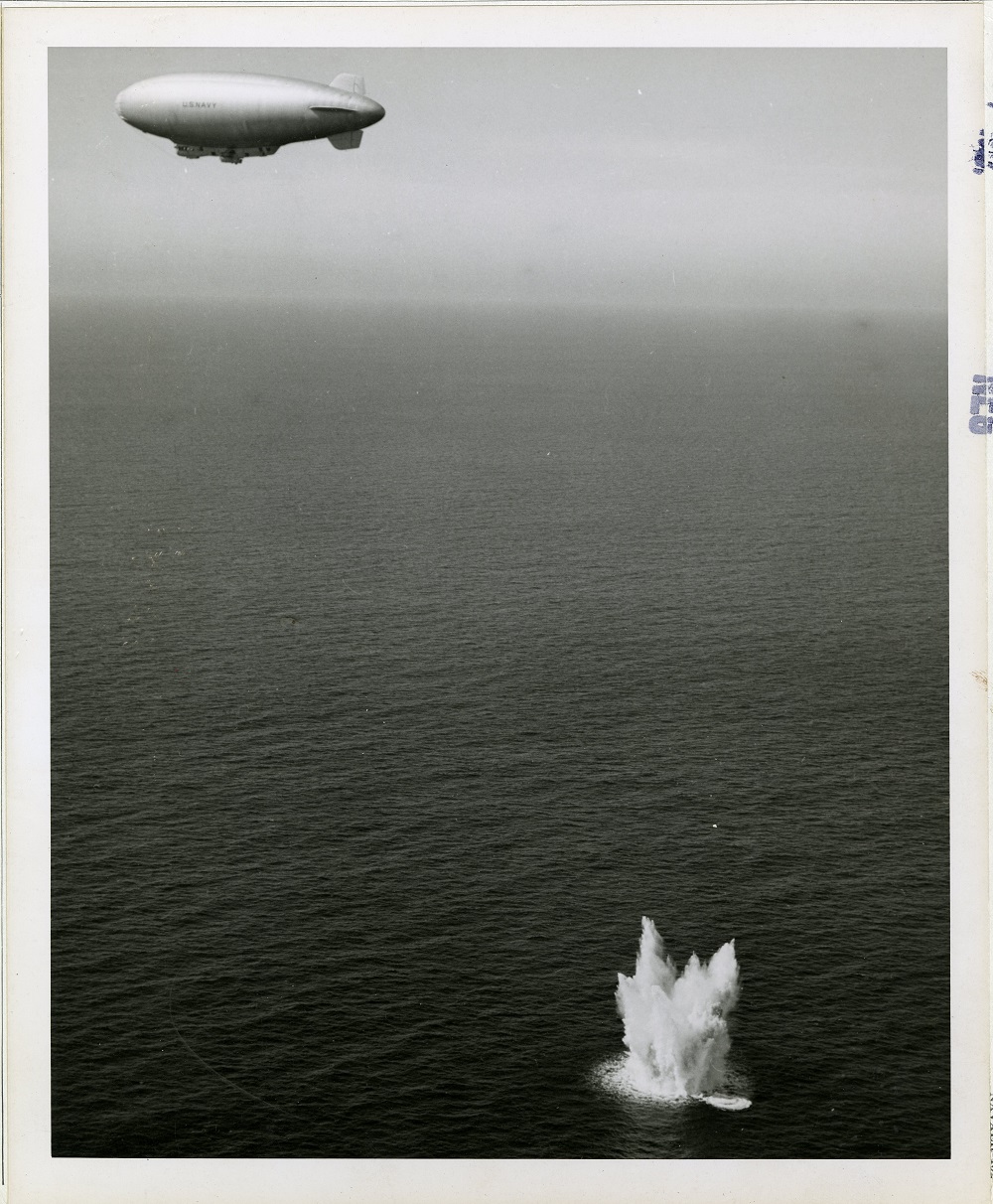

“M-Ship dropping bombs over ocean,” March 1944.

General Records of the Department of the Navy, National ArchivesUnlike rigid airships, which have an inner framework that houses lifting gas cells and is enveloped by doped, weatherproof fabric, blimps rely on the pressure of their lifting gas to maintain their iconic shape. These blimps were easier to build and disassemble but were significantly smaller and impractical for commercial travel. The United States Navy had a different purpose in mind when it placed its initial order with the Goodyear Aircraft Company.

Equipped with radar and armed with guns, scatter bombs, and depth charges, and capable of operating for 24 hours without resupply, blimps proved to be an effective coastal monitor against German and Japanese submarines and served in the Americas as well as the Mediterranean.

Often called “K-Ships” after the most prolific Navy blimp class, these vessels patrolled coastlines and escorted convoys. In 1942, German U-boats sank 63 vessels off the east coast of the United States. Succeeding years saw that number fall to three or fewer, nearly ending submarine predation of ships within sight of the U.S. coast.

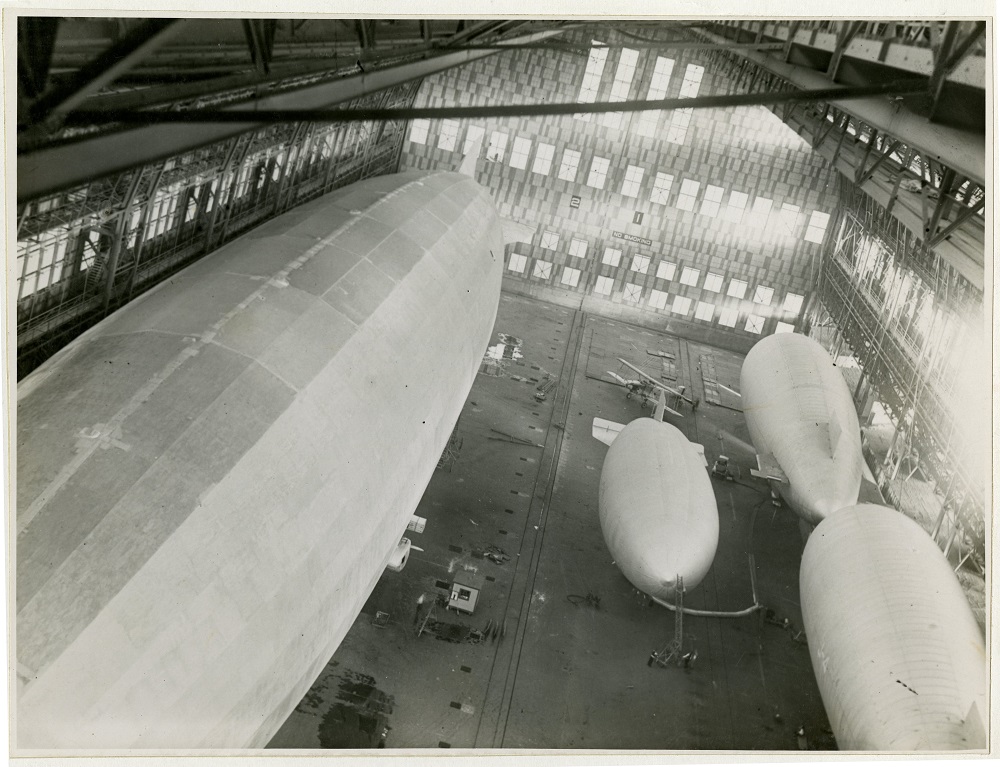

USS Los Angeles (ZR-3), F-3, F-4, and J-3 at NAS Lakehurst in 1928. For comparison to the K-ships, the F-types at 220,000 cubic feet have just over half the volume of a K-type.

General Records of the Department of the Navy, National ArchivesThe U.S. Navy blimps were divided into five fleet airship wings headquartered in Naval Air Stations (NAS) in New Jersey, Florida, Texas, California, and other fields in Trinidad and Brazil.

With envelopes of over 420,000 cubic feet for every one of the 134 K-Types and 635,000 cubic feet for the four M-Types, hangars originally built for the U.S. rigid airships program could not accommodate the girth.

Congress approved the construction of additional hangars in 50 bases. Originally designed to be made of metal, wartime shortages necessitated construction with lumber. This was undoubtedly a factor in the fiery destruction of several hangars in Richmond, FL, following a 1945 hurricane.

Many hangars built before and during World War II remain and may be used in innovative ways: the Mythbusters of the eponymous Discovery Channel series used one such hanger at the former NAS Moffet Field in Mountain View, CA, to test several myths.

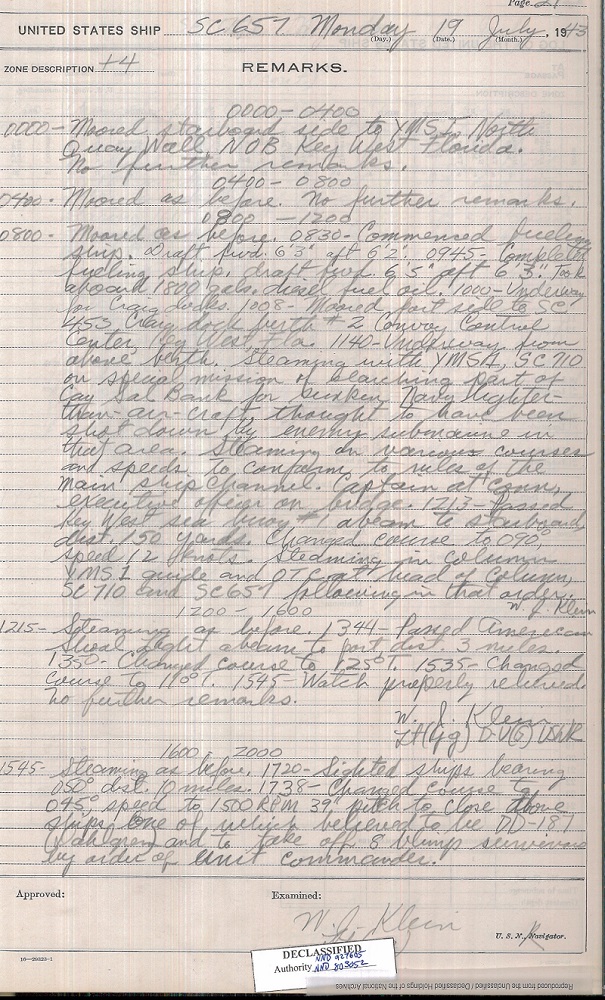

“Photography at Blimpron 14,” page 18.

General Records of the Department of the Navy, National ArchivesNAS Richmond was the home of squadron ZP-21 and the blimp K-74, the only U.S. blimp lost to enemy action. On July 18, 1943, the blimp spotted U-134 off Florida’s southern tip. Just before midnight, K-74’s radar detected what they would soon discover was a surfaced U-boat bearing southwest at 15–18 knots. Fearing imminent danger to shipping lanes, K-74’s command pilot Lt. Nelson Grills ordered an attack.

This defied convention, which dictated that blimps either direct airplanes and surface ships or attack submarines when submerged. After several exchanges with machine guns, depth charges, and the U-boat’s deck gun, the K-74 crashed. Fearing that the remaining depth charges would explode, the 10 uninjured crew left the crashed blimp. Lieutenant Grills returned and remained with the ship for several hours and, having lost sight of his crew, began swimming to the Florida Keys.

Submarine chaser 657 (SC-657) logs at 1140 on July 19, 1943, state that it is on a “special mission” for a “sunken Navy lighter-than-air-craft.” They found Lieutenant Grills in “exhausted” condition.

Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, National ArchivesAt some point in the morning of July 19, U-134’s crew was able to inspect the still floating remains of K-74 and photograph it. A German radio log indicates the crew mentioned shooting down an airship and suffering damage to its diving tanks but nothing about the photographs. U-134 was sunk a month later off the Spanish coast but not before passing on the K-74 photographs to another vessel.

Grills was rescued by submarine chaser SC-657 while eight of his nine surviving crew were rescued by the destroyer USS Dahlgren. Isadore Stessel, aviation machinist’s mate second class, died minutes before rescue. He is only U.S. Navy airshipman to die from enemy action in the over 55,900 total missions and 550,000 hours. In contrast, German airship crews in World War I endured a 40-percent casualty rate and the loss of 79 ships out of 123.

Airships have for decades been subjects in speculative fiction or an embodiment of man’s hubris. Large, impractical, dangerous—the airships of the early 20th century are exemplars of an old-fashioned vision for the future where, for one reason or another, heavier-than-air flight doesn’t quite take off.

This dismissal as a fad ignores the crucial role of lighter-than-air dirigibles in World War II and their current relevance in military and civilian applications.

The National Archives has photographs, videos, schematics, war diaries, and after-action reports documenting the development, training, and operations of airships.

Source: The National Archives – archives.gov