Source: BBC News Magazine – bbc.com

Source: BBC News Magazine – bbc.com

By Justin Parkinson

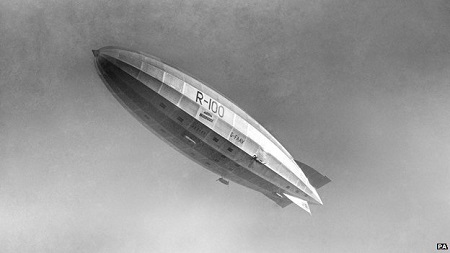

Britain was seen to lag behind other countries during the global airship-building race of the 1920s and 1930s. But a quirky scientific experiment 85 years ago briefly gave a boost to the image of the giant aircraft.

As airship R100 crossed the Atlantic on its maiden voyage, the captain stuck his arm out of the window. In his rubber-gloved hand was a round piece of glass.

Every three hours during the trip from England to Canada, Squadron Leader Ralph Sleigh Booth, or another member of the 44-man crew, repeated the action, for five minutes at a time.

A couple of thousand feet below, a passenger on a steam ship heading in the same direction, Lester Dillon Weston, watched with great interest through a telescope pushed through his porthole. Booth was carrying out an experiment aimed at ensuring the human race could continue to feed itself. The piece of glass was a Petri dish designed to pick up spores released by a fungus known as wheat rust, which had destroyed large areas of crops in North America.

Cambridge University scientist Dillon Weston – a man with a passion for aviation – was keen to find out whether spores could cross the Atlantic. He decided to use airships, still at the experimental stage as passenger craft, to aid his research.

“It wasn’t just Dillon Weston who benefited from this,” says Ruth Horry, a researcher at Cambridge University’s history and philosophy of science department. “People were suffering a sort of airship fatigue in Britain. The government had spent lots of money on developing them and nothing seemed to be coming out of it.

“So the fact they could be used to aid scientific endeavor was very useful for publicity. That’s why the captain took part in the experiment. It was excellent PR.”

Airships, quiet but huge, had not always been popular with Britons. Germany had used them to drop bombs on Britain during World War One. After one was shot down over Cuffley, Hertfordshire, in 1916, the pilot responsible, William Leefe Robinson, was awarded £3,500 and a Victoria Cross.

In contrast, after the war, the government became involved in efforts to turn airships into luxurious passenger craft, able to compete with ocean liners and linking the British Empire more quickly. It was envisaged that they could get from England to Australia in 10 days, India in six and Canada in three. Cruising speeds were lower than those for aeroplanes but during this era using the latter was expensive and involved many stop-offs.

“The public was pretty much in favor of airships,” says airship historian Dan Grossman. “I don’t think people were tired of them by 1930 but maybe that there was a sense that the British effort could move on a bit quicker.”

Other countries’ programs had resulted in tales of bravery which enthralled the public. In 1926, the airship Norge became the first aircraft to reach the North Pole, on an expedition organized by Norwegian Roald Amundsen and American Lincoln Ellsworth. Germany’s LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin had made a five-stage flight around the world in 1929, amid huge press coverage – unsurprising as media mogul William Randolph Hearst was the tour’s major backer.

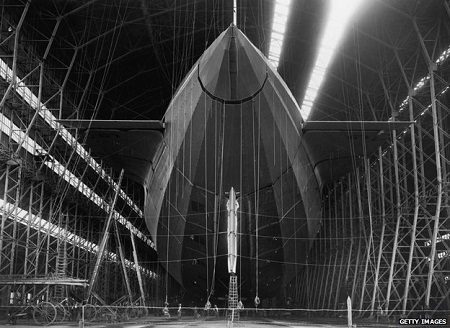

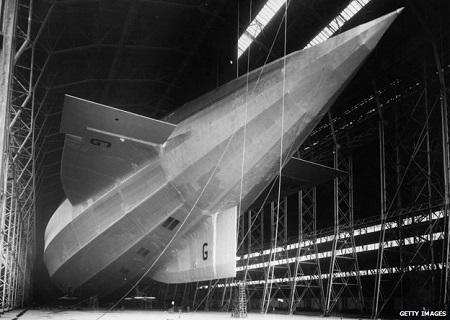

The 720ft-long R100, built by Vickers at Howden, East Yorkshire, set off from Cardington, Bedfordshire, in July 1930. Its inflated volume was more than five million cubic feet and its construction involved 58,200ft of tubing and five million rivets.

Its opulent design included a double staircase leading down to the dining room, flanked by panoramic windows, and a two-tier promenade deck. It could carry 100 passengers, sleeping in bunk beds, and had a nautical theme, with the use of portholes as windows. The official brochure described the R100 as like a “small hotel” and “intermediate in comfort between a Pullman coach and ocean liner”.

Costing about £450,000 to build and run, the maiden voyage coincided with Dillon Weston’s trip to Canada for a year-long study of the effects of fungi on crops.

Dillon Weston persuaded those in charge of Sqn Ldr Booth’s mission to assist his experiment. As a former member of the Cambridge University Air Squadron, he had previously badgered friends to fly around Cambridgeshire in planes to test his Vaseline-coated collection dishes. His involvement in the R100 voyage was timely for the government, as it gave it an added note of practicality.

“Devastating yet invisible plant diseases were an important enemy to conquer and new aviation technologies were vital in winning the war against them,” says Horry. “Newspaper coverage of the time showed that the scientist who chased invisible diseases captured both tiny spores and the imagination of the public. ‘Disease germs two miles up – flying scientists chase them,’ declared one newspaper.”

Fitters and crew on top of the airship R100, during construction at Howden, East Yorkshire.

Photo courtesy of BBC.com“No plane would have been able to carry the equipment needed for any scientific expedition across the Atlantic at that stage, so the airship was vital,” says Grossman.

Dillon Weston watched some of the flight from below, but the 64mph cruising speed of the R100 was far greater than that of the Ausonia, on which he sailed. The R100 took just over three days to travel from Bedfordshire to Montreal, where 100,000 people came to see it. The Toronto Star newspaper christened it a “wonder airship” and the Manchester Evening News called it a “beautiful sight, the sun glinting brilliantly” on its hull.

The R100 was nicknamed the “capitalist airship” because a private firm had built it, while its sister ship, the R101, became known as the “socialist airship”, having been constructed by the Air Ministry, although both were to transport only wealthy travelers. The R101, despite the proximity of millions of cubic feet of hydrogen, had a smoking room on the lower deck. The floor and ceiling were made of light asbestos.

When he arrived in Canada, Dillon Weston collected the Petri dishes to analyze, for what he thought was the start of a series of experiments. But this was not what happened.

On 5 October 1930, the R101 crashed near Beauvais, northern France, en route to Karachi. The hydrogen ignited, killing 48 of the 55 passengers and crew. Among them were aviation minister Lord Thomson of Cardington, who had pushed for the government to promote airship building, and his valet.

Grossman feels Thomson was partly to blame for demanding the R101’s launch before sufficient testing. Having arranged an official dinner at the planned stop-off point in Ismalia, Egypt, Thomson decided against refueling there, to avoid eating amid noxious smells. This meant overfilling the balloon, Grossman argues, meaning more rubbing on girders and hydrogen leakages. Thomson also reportedly brought a 129lb carpet and two cases of champagne, weighing 52lbs, on board.

The crash was a PR disaster, with pictures of the site splashed across newspapers and survivors appearing fully bandaged in photographs.

The British Airships Scheme was abandoned with what the historian Nick le Neve Walmsley has called “extraordinary haste”, with the R100 being scrapped. Manned airships programs largely ended after the German Hindenburg crashed at Lakehurst, New Jersey, in May 1937, with the loss of 35 of those on board.

Dillon Weston, who died in 1952, used a Bunsen burner to create glass models of the spores he analyzed, which can be seen at the Whipple Museum of the History of Science in Cambridge. He never wrote his full report, not considering the evidence gained from the R100 conclusive on the movements of wheat rust spores. But Horry has used flight papers, telegrams, family letters and newspaper reports to re-trace his journey.

Although Dillon Weston’s experiment was never repeated, Horry believes its “piggy-backing” spirit continues in NASA’s gathering of peripheral scientific data on its missions. “It sounds brave to stick an arm out of an airship window,” she says. “But really, like going into space, the brave thing was flying the airship in the first place.”

Source: BBC News Magazine – bbc.com