Source: Akron Beacon Journal – ohio.com

Source: Akron Beacon Journal – ohio.com

By Mark J. Price

One of the lesser-known stories of World War I is the naval invasion of Fritch’s Lake.

The Suffield Township pond, named for Portage County settlers John and Mary Fritch, served as a command post 100 years ago in the battle for air supremacy. We know it today by a different name.

Akron’s Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. purchased 720 acres in 1916, including the spring-fed lake, with plans to develop a flying field. Just before the United States entered the Great War in 1917, the Navy contracted with Goodyear to build nine blimps to patrol the U.S. coast and perform anti-submarine duties.

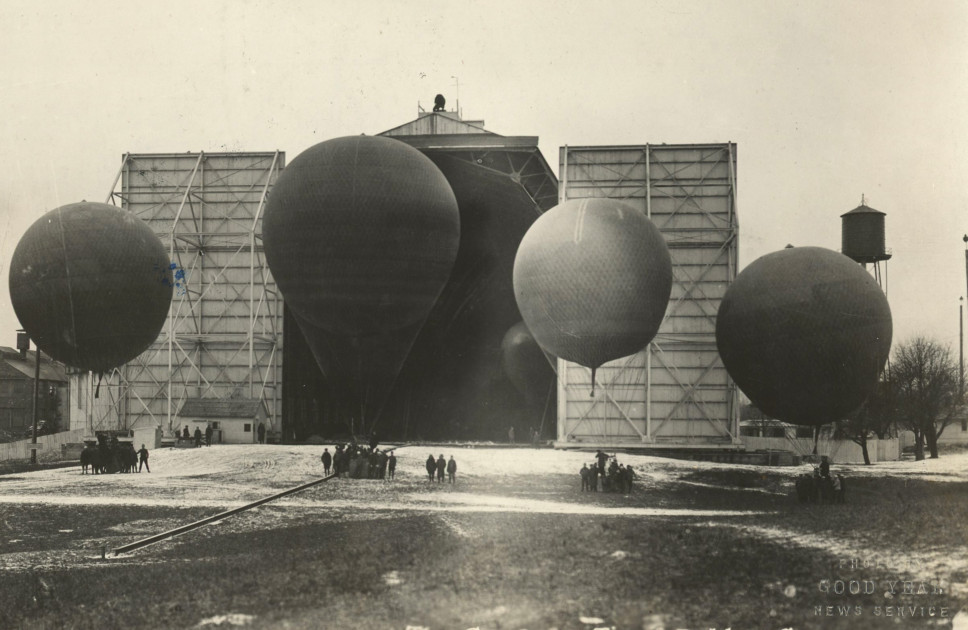

Lighter-than-air pilots receive balloon training at the Wingfoot Lake hangar during World War I. About 600 Navy and Army officers learned to fly and maintain airships and balloons during the war.

Credit: Akron Beacon Journal/Ohio.com file photoThe Navy took over Fritch’s Lake site and turned the adjacent land into an airship training station during the war. Over the next few years, Goodyear aeronautical experts trained about 600 Navy and Army officers to fly and maintain blimps, observation balloons and barrage balloons.

“Cadet officers from Army and Navy, in olive drab and forest green, poured into Akron from primary training schools at Cornell and MIT to take flight instruction at the lake, with Goodyear men as instructors,” Goodyear historian Hugh Allen recalled.

A Goodyear-built airship glides over Fritch’s Lake while preparing to make a landing at the U.S. naval station in Suffield Township during World War I. Today the body of water is known as Wingfoot Lake.

Credit: Akron Beacon Journal/Ohio.com file photoThe complex was nicknamed “The Kitty Hawk of Lighter-Than-Air.” The body of water was renamed Wingfoot Lake in honor of Goodyear’s Mercury-heeled logo.

Workers constructed a military base that included nearly 30 buildings, including a 150-man barracks, officers quarters, operations center, a power plant, commissary, bathhouse, fire station, hospital, superintendent’s office and guardhouses.

Rising above the complex was an air hangar that initially measured 100 feet wide, 90 feet high and 200 feet long. Military personnel soon realized that the building was too small and doubled its length to 400 feet. The steam-heated building housed a mechanical hoist, balloon winch, blower fans, motors and other equipment.

For lighter-than-air flight, the Wingfoot Lake station built a hydrogen plant that included compressors, scrubbers, purifiers, exhausters and steel bottles to contain the buoyant, explosive gas.

Famed Goodyear balloonist Ralph H. Upson served as superintendent of aircraft production. Aeronautical engineer Charles H. Roth and pilot R.A.D. Preston taught classes on the fundamentals of ballooning.

Naval aviator George Crompton, one of the earliest students, recalled of Fritch’s Lake: “We were 12 cadets, seven from Harvard, others from various places, I was the youngest, 20 years old. Colley Bell, a lawyer, the oldest, 30 years old. ‘Those damn boys,’ he called us.

“Various commissioned officers of the U.S. Navy appeared and disappeared from time to time, receiving ‘instruction’ how to fly the dirigibles but Lt. Louis H. Maxfield, U.S.N, was the commanding officer all the time. Ensign Frederick Paul Culbert, U.S.N., the junior officer, was disciplinary officer. He had charge of us. Excepting for the executive officer, the other officers had nothing to do except to study. I supposed they played bridge.”

Cadets took courses on atmospheric pressure, expansibility of gases, isothermal conditions and other conditions. They learned the finer points of barometers, stratoscopes, anemometers, barographs, speedometers and compasses.

And they flew. They flew a lot. The adventures were legendary.

On Dec. 22, 1917, Ralph Upson and four passengers made a chilly night flight in a balloon, lifting off in Suffield at 7 p.m., passing Cleveland at 9, floating over the dark waters of Lake Erie and spying a Canadian lighthouse at 1 a.m. They set down in a pasture at 3:30 a.m. to sleep and then continued on to Toronto, where they landed at 11:15 before returning home.

“The average speed was about 20 miles an hour, and the highest altitude 9,000 feet,” the Medina Sentinel reported. “The men encountered a snowstorm Sunday afternoon at an altitude of 8,000 feet, the reflection from the snow resembling a mirror. At one time while crossing the lake, the end of the balloon rope trailed through the water.”

One morning in July 1918, Stark County farmer John Fasnacht heard a knock at his door at 5 o’clock and welcomed six aviators who had landed in his field. They asked if they could borrow his Ford automobile to drive to Canton.

“This was given by Fasnacht who cheerfully brought the soldier boys to Canton after having given them a real old-fashioned Stark County breakfast of fresh butter, milk and eggs,” the Canton Daily News reported. “Fasnacht was very proud of the opportunity afforded him to treat these visitors who represented Uncle Sam.”

Then, as now, blimp sightings created a commotion across Ohio. The whir of motors had all eyes looking up. In August 1918, a Goodyear airship thrilled Massillon with a surprise appearance during afternoon training.

“Flying extremely low over the heart of the city, a dirigible balloon from Wingfoot Lake paid a visit here about 3:30 o’clock Tuesday afternoon,” the Massillon Independent reported. “The crew could be plainly discerned learning over the edge of the basket, shouting greetings to the onlookers as they hummed along.”

During the first three years, the station logged 3,281 flights, 10,235 passengers and 60,760 miles. After the war, the 59th Dirigible Balloon Company moved from Fort Omaha, Neb., to Wingfoot Lake. New barracks and officers quarters were built.

The early days of lighter-than-air aviation gave Akron its iconic Goodyear blimp, which is still based at Wingfoot Lake.

Lt. Cmdr. Zachary Lansdowne was the last commanding officer at Wingfoot Lake before the Navy turned the station over to Goodyear in 1922. Tragically, Lansdowne died in the 1925 crash of the dirigible USS Shenandoah in Ava, Ohio. Lt. Lewis H. Maxfield, the station’s first commander, died in 1921 when the British airship ZR-2 crashed near Hull, England.

In 1955, the Rev. William L. Fisher, pastor of United Church of Akron, presided over a memorial service to the balloon men who died in World War I.

“They had the highest type of adventurous spirit,” he said. “We should not mourn them today. They have simply made another ascension, only this time they went a little higher and will stay longer.”

Source: Akron Beacon Journal – ohio.com